By Colin Konschak, FACHE and Dave Levin, MD

A Framework for Innovation

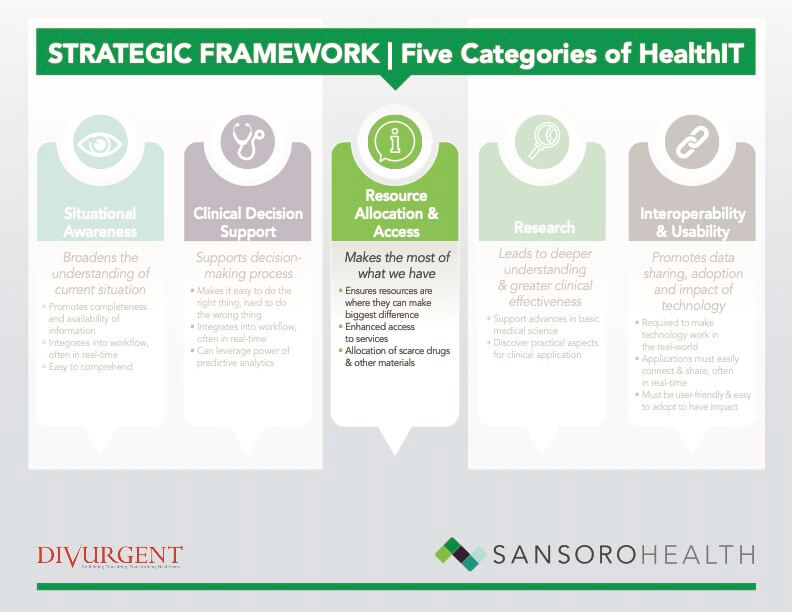

In part one of our series, we declared the opioid crisis an “All Hands-On Deck” moment and made the case that health IT (HIT) has a lot to offer. Given the many different possibilities, having a method for organizing and prioritizing potential IT innovations is an important starting point. We have proposed a framework that groups opportunities based on an abstract view of five types of functionality. In this article, with an assist from Dr. Marv Seppala, Chief Medical Officer at the Hazelden-Betty Ford Foundation and Dr. Krista Dobbie, Palliative Care physician at the Cleveland Clinic, we will explore allocation of resources and access to care and the role that

technology can play.

Resource Allocation and Access for Opioid Management

Supply and Demand

There is almost always an imbalance between what we need (demand) what we have (supply) in healthcare. This ever-present imbalance between supply and demand inevitably and regularly leads us grappling with how to wisely allocate precious resources. The opioid crisis is no exception and is a good window into the general challenge of resource allocation in healthcare. Fortunately, technology (both information tech and life sciences) can help navigate these challenges efficiently and effectively.

There is almost always an imbalance between what we need (demand) what we have (supply) in healthcare. This ever-present imbalance between supply and demand inevitably and regularly leads us grappling with how to wisely allocate precious resources. The opioid crisis is no exception and is a good window into the general challenge of resource allocation in healthcare. Fortunately, technology (both information tech and life sciences) can help navigate these challenges efficiently and effectively.

What exactly do we mean by “resources”? For the purposes of this paper, we break this down into two groups: people and materials. As we will see, when it comes to people, this is mostly about access to care in a timely, effective and efficient manner. Materials can encompass many things, but we primarily will focus on drugs, testing and the like. In both cases, there are instances of underuse, overuse, shortages, and misallocation which point towards ample opportunity for improvement.

Access to Care

Timely access to appropriate care is essential in dealing with the opioid abuse crisis – just as it is for many diseases. The vast majority of this care involves patients having access to and interacting with a variety of providers. “The first thing that comes to mind when I think about shortages and access is providers,” says Dr. Seppala. This shortage includes primary & specialty care, physicians and other licensed professionals. There is a heavy emphasis on Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) for addiction these days and this requires MD oversight. Physicians who specialize in addiction medicine are highly qualified to provide this oversight but are in short supply. Most primary care physicians, who could, in theory, provide this care, are reluctant to do so either due to lack of knowledge or concerns about the clinical and medical-legal consequences of bad outcomes like overdose or death. To make matters worse. Addiction specialists often have a personal preference for a broad-based practice that includes services besides MAT – services that could be provided by either primary care physicians or other clinical professionals. So, we have too few specialists practicing too broadly and too few primary care providers who are properly trained and confident in providing these services.

The potential solutions to these challenges can be drawn from similar ones in other areas of medicine:

- Optimize and maximize the impact of experts like addiction medicine specialists.

- Expand the capacity and capabilities of primary care providers.

- Enhance the referral and consultation process in ways that maximize the collaboration and impact of a combined primary-specialty care approach. The mantra here should be: everyone at ‘top of licensure’ so each professional is mostly doing things they are qualified to do.

Obviously, some of these challenges are more “geopolitical” than technical. For example, tech likely has little to offer when it comes to a medical specialist’s preference to practice broadly. However, there are a number of promising health IT opportunities here:

- Leverage analytics and scheduling applications to optimize scheduling to maximize access to the right provider at the right time.

- Enhance communication between various providers to support the provision of primary care and facilitate the timely identification and referral of patients who require higher levels of care.

- Expand educational opportunities for all providers to “raise their game” and comfort level in caring for these patients.

Telehealth

Telehealth is a proven way to extend access to care and holds great promise in addressing this crisis. According to Dr. Seppala, “Telehealth definitely helps but is limited to 1-to-1 interactions between the provider and patient. What we need now is a 1-to-many solution that supports group visits. “ This is a major tech gap that, assuming it is HIPPA and CFR Part 42 compliant, could have a major positive impact that goes beyond simply expanding capacity. As Dr. Seppala pointed out, “There is a proven, special value in group visits. This disease undermines the brain’s ability to recognize that one has the disease. This goes far beyond simple denial and is a function of the disease itself. But these patients can recognize it in other people in the group and that can lead to the important breakthrough of self-recognition.”

Efficient Use of Material Resources

Material resources refer to things like drugs, diagnostic testing, etc. They are the non-people part of our resources and they too are subject to misallocation, overuse, and underuse. As in many other industries, enhanced supply chain management applications can play a transformative role in the allocation of materials. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg in this area.

Fortunately, with rare exceptions, the main drugs used to treat opioid addiction are readily available and covered by insurance. However, as is often the case, newer drugs tend to be in shorter supply and much more expensive. They are also subject to stricter control by insurance companies and usually require prior authorization. Lack of insurance coverage or self-pay situations can place these drugs out of reach. This isn’t unique to the opioid crisis. Regardless, more efficient authorization processes, easier access to drug payment programs and provider adherence to best-practice treatment protocols backed up by clinical decision support – all of which can be IT-enabled – provide opportunities for further improvement.

The Other Side of the Coin: A Palliative Care PerspectiveIt’s important to remember that opioids do have an important and valid place in patient care. To learn more about this perspective, we spoke with Dr. Krista Dobbie an experienced palliative care physician at the Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Dobbie, of course, is concerned about the opioid abuse epidemic but also pointed out that use of opioids is a mainstay of effective pain management in palliative and end-of-life (EOL) care. As is often the case, it’s about context, clinical knowledge, and the specific patient and their needs; In a word: judgment. When it comes to access and allocation, she notes a couple of challenges that have arisen in providing palliative care as a result of well-intended attempts to address opioid abuse. For example, it has become more difficult to get cancer and other palliative care patients the medications they need. Some of the new hurdles are administrative. For example, morphine for cancer patients previously did not require prior authorization since this it is considered first-line treatment in this population. Some payers now require prior authorization which increases administrative burden and can result in delays in care. In addition to the direct clinical impact on the patient, this can lead to extended hospital stays as inpatients wait for prior-authorization of these vital medications before they can be discharged. Dr. Dobbie states there are, “More hoops than ever – even with cancer patients” and notes that pharmacists and some insurance companies refuse to fill prescriptions out of, in these cases, misguided concerns about dose, duration, or amount dispensed. From a materials perspective, there have also been reports of outright shortages of vital pain drugs due to production issues. Dr. Dobbie recalled previous periods of time when there were shortages of intravenous pain meds for hospitalized patients which forced providers into tight restrictions and careful allocation of the limited supply. On the plus side, Dr. Dobbie sees that heightened awareness has increased screening for palliative medicine patients who may be at high risk for misusing or abusing opiates. Most patients are signing treatment contracts outlining opiate risks. These contracts also state that there must not be any misuse or diversion of drugs. Routine drug screening is utilized to ensure patients are using medications appropriately. If the clinician is concerned, the situation can be investigated further, and team conferences can be leveraged to evaluate and plan interventions. |

Another resource to consider is diagnostic testing. Dr. Seppala pointed to urine drug screening (UDS) as an area ripe for improvement. To start with, UDS tests have known limits. Lower cost, urine screening can only detect some drugs for a short time after they’ve been used leading to false negative results. Other UDS methods only test for prescription drugs missing a major cause of the opioid crisis – the migration-use of street drugs like heroin. More sophisticated tests can overcome these limits but are more expensive and time-consuming. Adopting a tiered approach based on evidence is best. Better education, distribution of best-practice protocols coupled with decision support are potential avenues where health IT can contribute. Advances in clinical testing hold out hope as well.

According to Dr. Seppala, UDS also provides an interesting window into overuse, another form of inefficient allocation. This is mostly a story of unscrupulous providers taking advantage of patients and arguably, committing insurance fraud. The typical scenario plays out in low cost, “sober housing” settings. In a kind of bait-and-switch, these providers set low base fees to attract patients. They then overuse tests like UDS by ordering too many and directing the samples to their owned labs where they charge high fees. Dr. Seppla says insurance companies and State attorneys general have woken up to this and are beginning to pursue.

In the face of deliberate fraud, testing protocols and CDS will be of limited value. Of course, in value-based reimbursement models, the incentive is to avoid wasteful overuse since that decreases provider profits.

Big data analytics may hold some answers to these behavior-based challenges. It is not hard to envision a future where the same AI techniques that look for potentially “bad” credit card charges and flag them for further attention could be applied to many of the challenges outlined above. This kind of profiling has the potential to find unusual or suspicious patterns while also recognizing legitimate differences in practice between say, an advance pain expert like Dr. Dobbie and the garden variety primary care physician.

What’s Next

The next article in this series will look at the role technology can play in supporting and enhancing medical research into opioid abuse and addiction.

About the Authors

Dave Levin, MD is the Chief Medical Officer for Sansoro Health where he focuses on bringing true interoperability to health care. Dave is a nationally recognized speaker, author, and the former CMIO for the Cleveland Clinic. He has served in a variety of leadership and advisory roles for health IT companies, health systems, and investors. You can follow him @DaveLevinMD or email Dave.Levin@SansoroHealth.com

Colin Konschak, RPh, MBA, FACHE is the Chief Executive Officer at Divurgent. Colin is a Registered Pharmacist and is a highly accomplished executive with over 20 years of experience with extensive experience in health care operations, P&L management, account management, strategic planning and alliance management. You can follow him on LinkedIn or email him at ck@divurgent.com.